The Aeropilates Clinical Study White paper

AeroPilates Pro XP 555 Study

The Fitness Effects of A Combined Aerobic and Pilates Program

An Eight-Week Study Using The Stamina AeroPilates Pro XP555

Neil Wolkodoff, PhD, Sue Peterson, Jeff Miller, PhD

Abstract

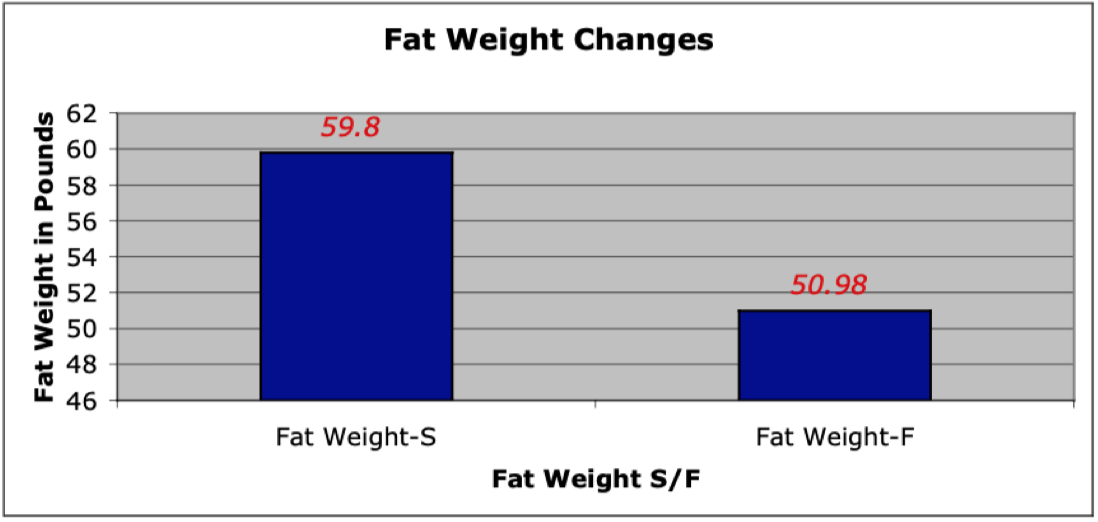

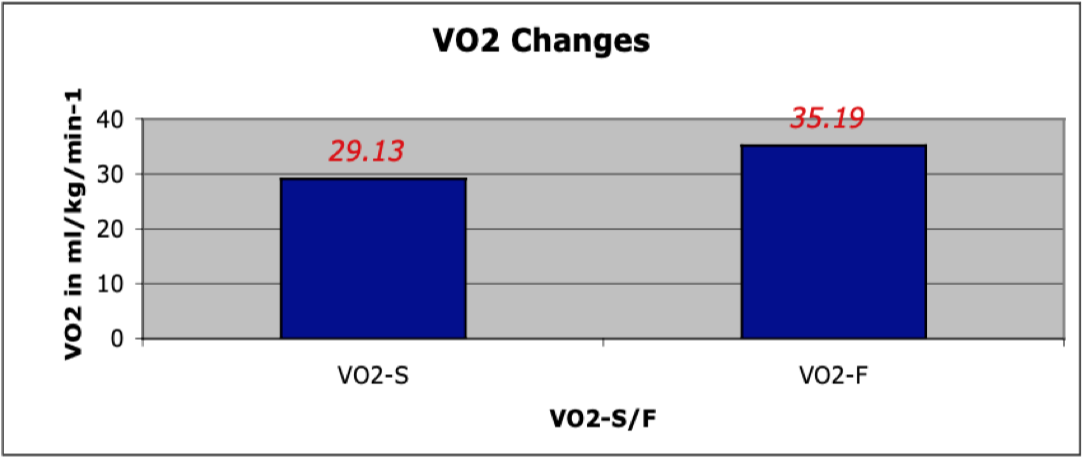

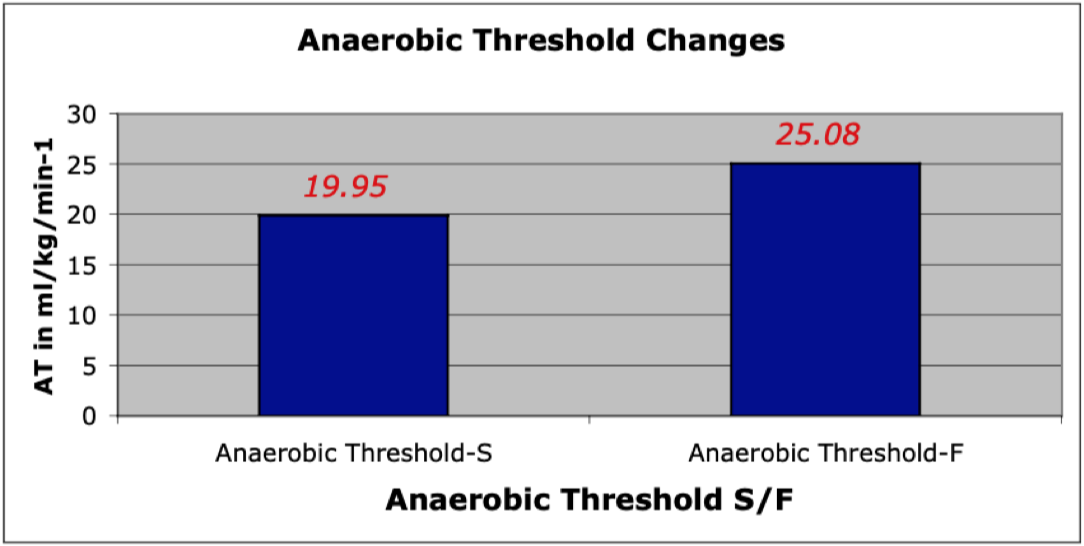

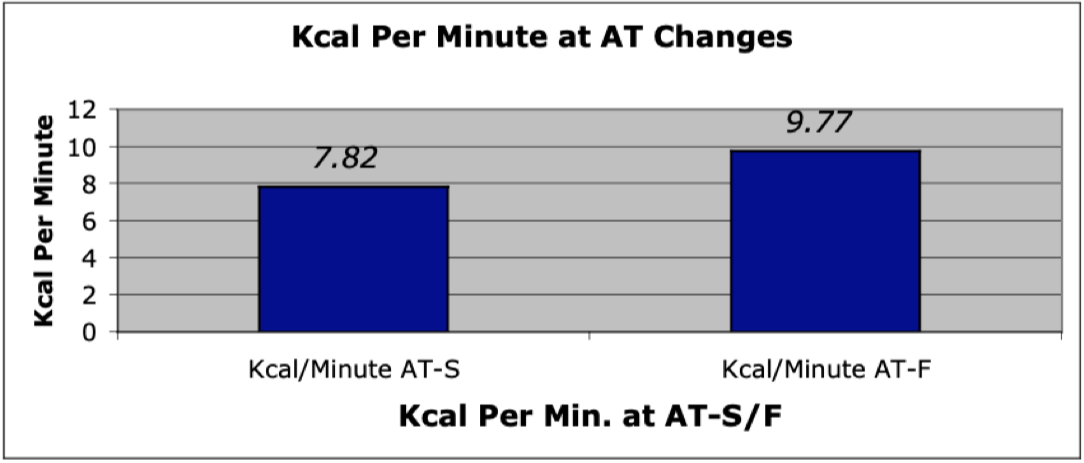

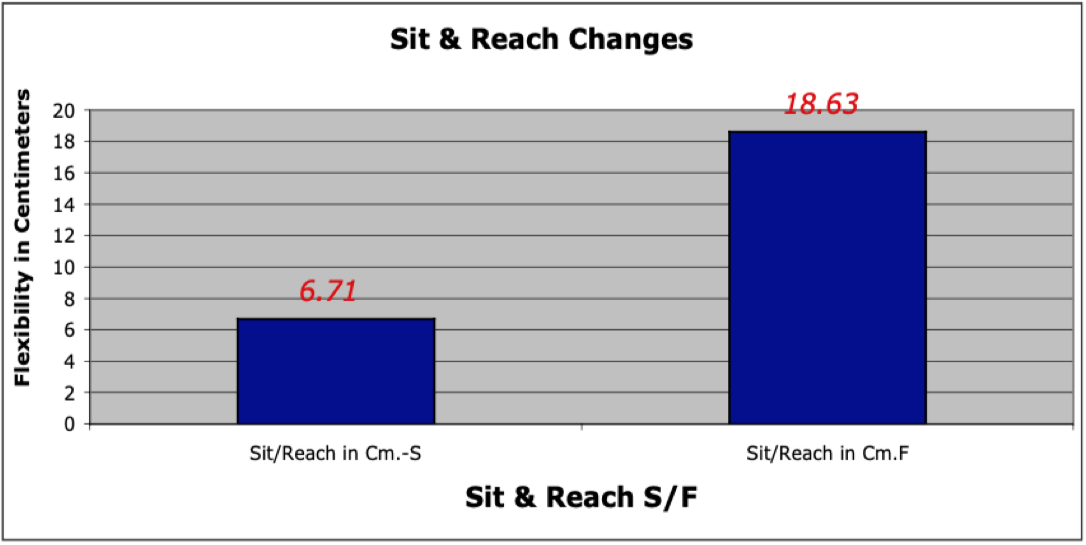

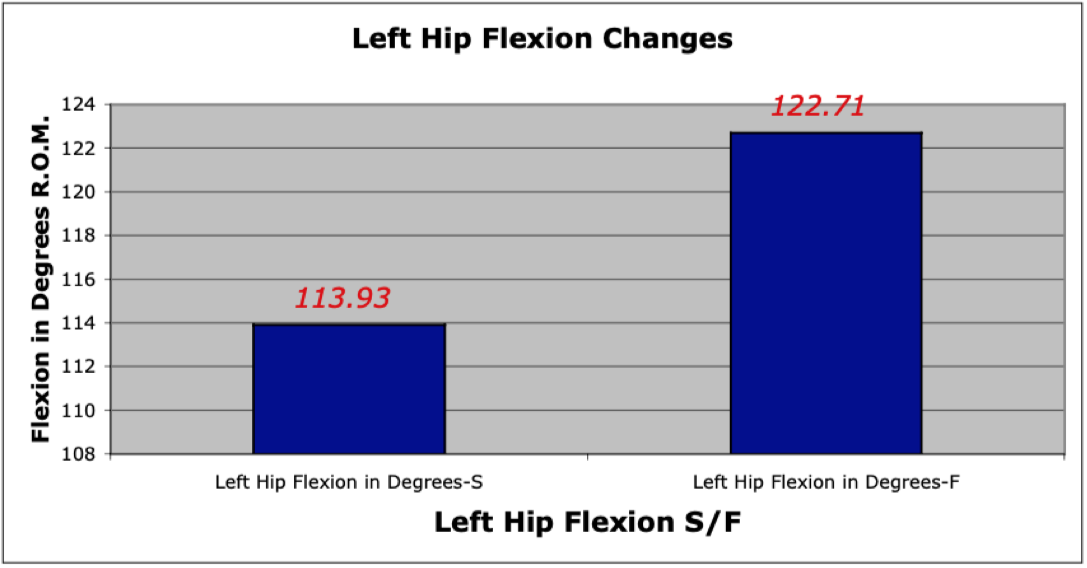

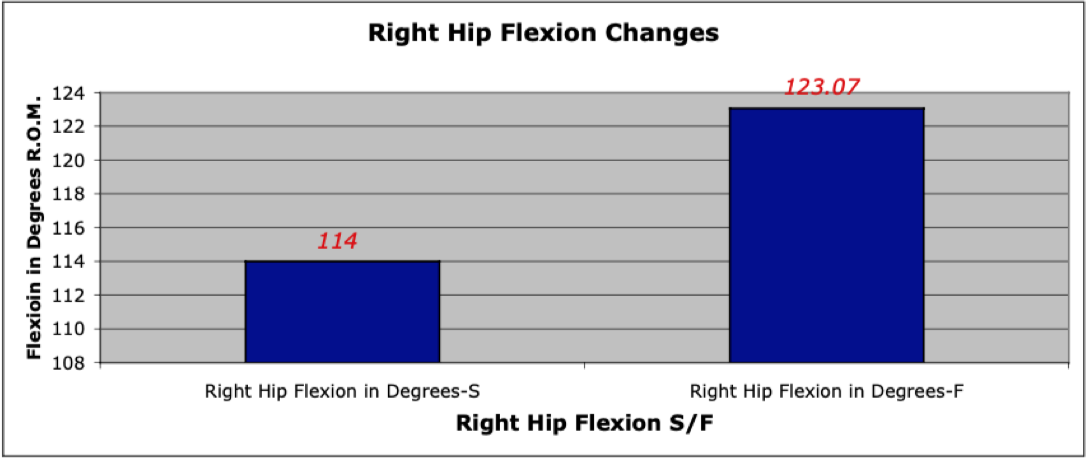

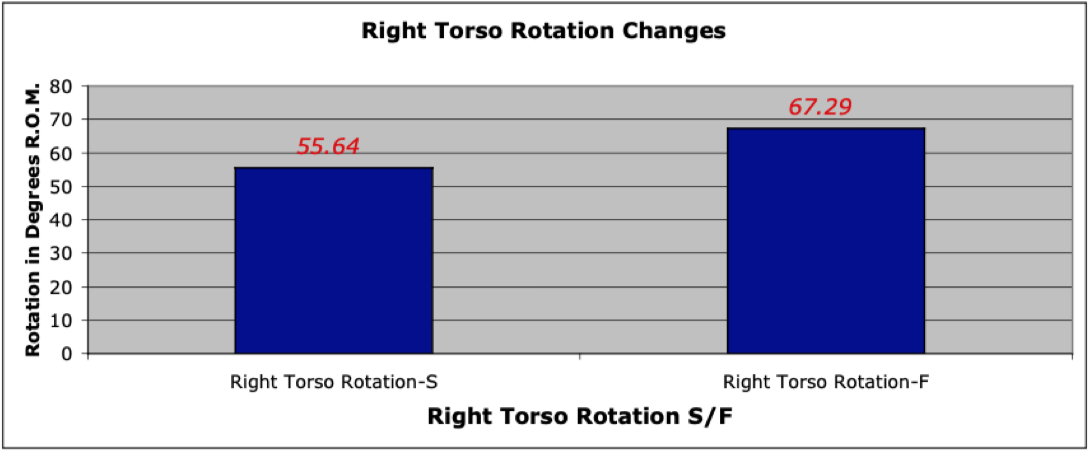

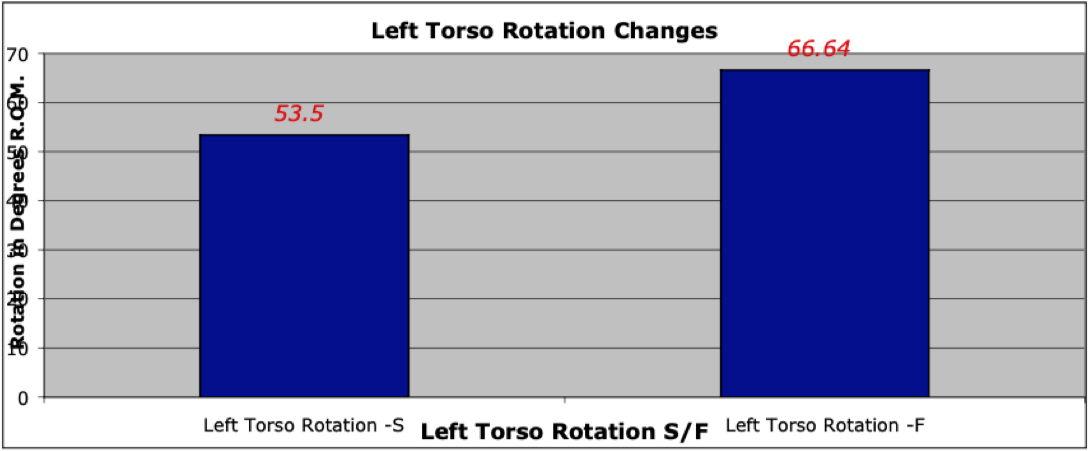

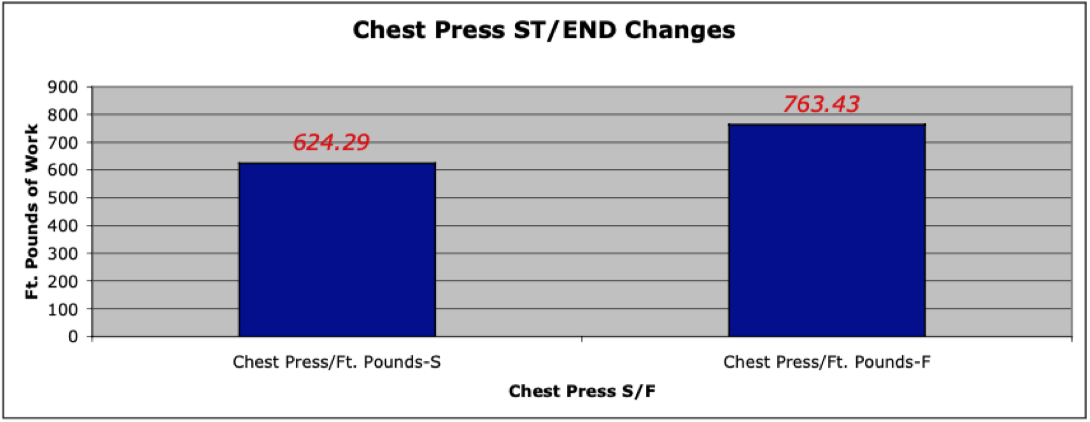

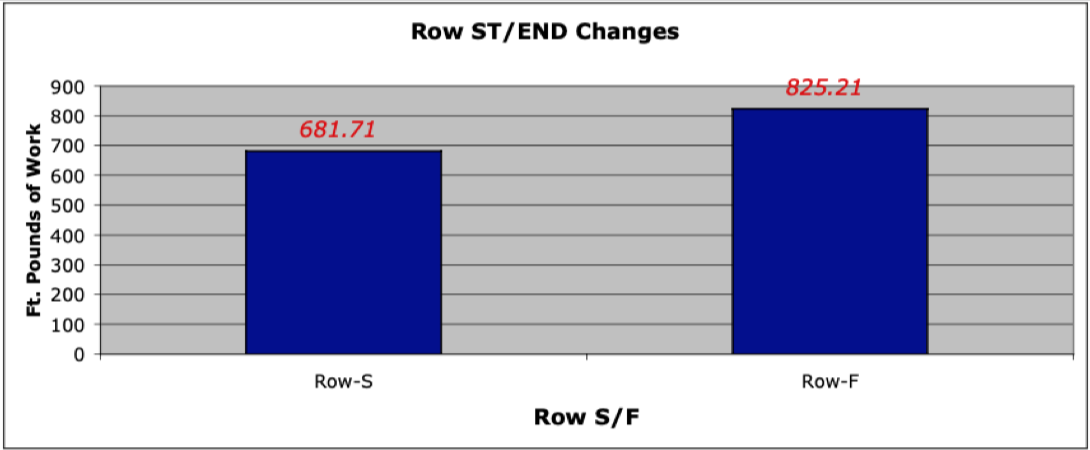

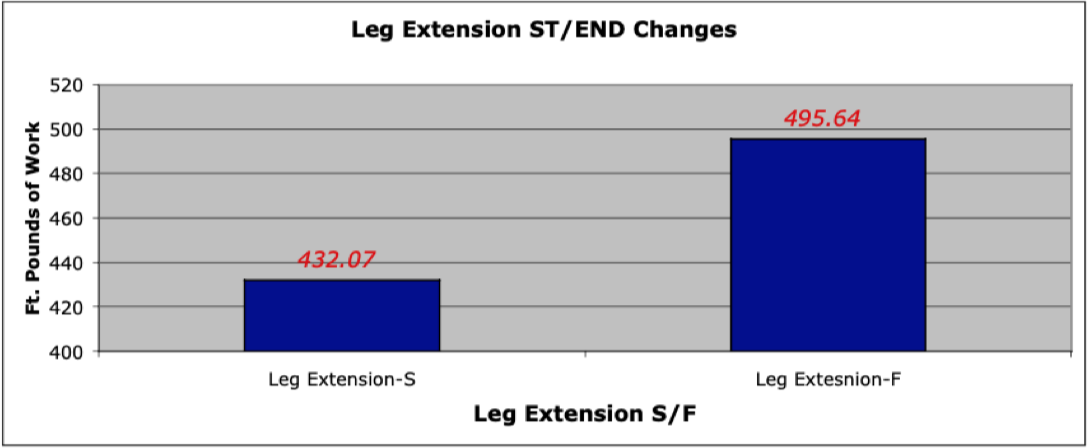

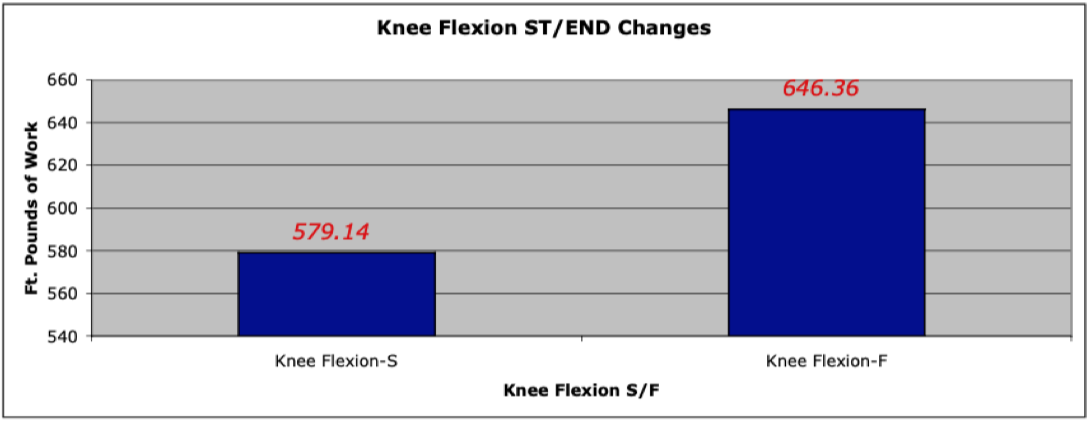

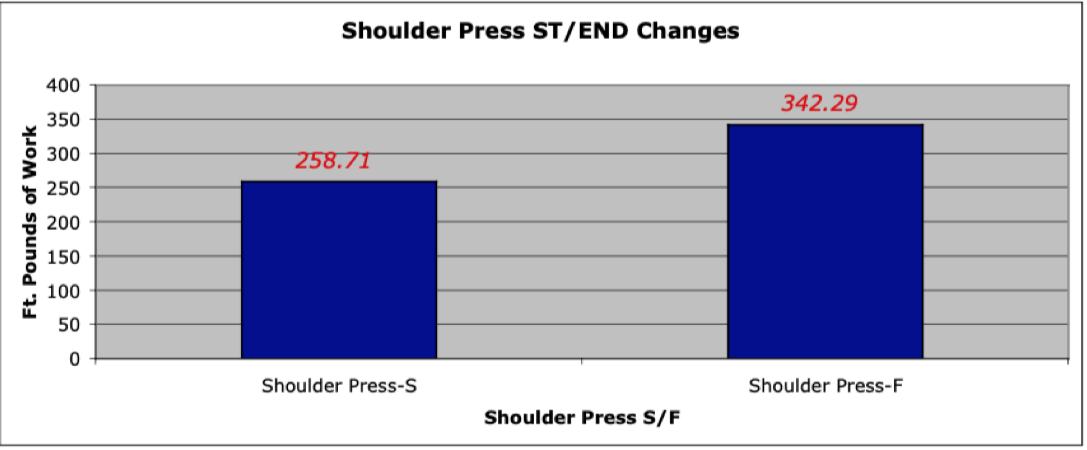

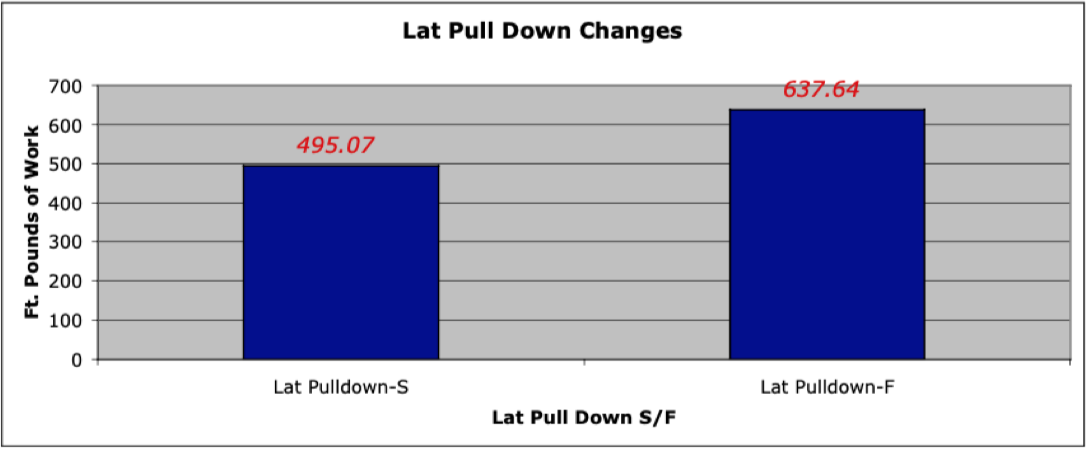

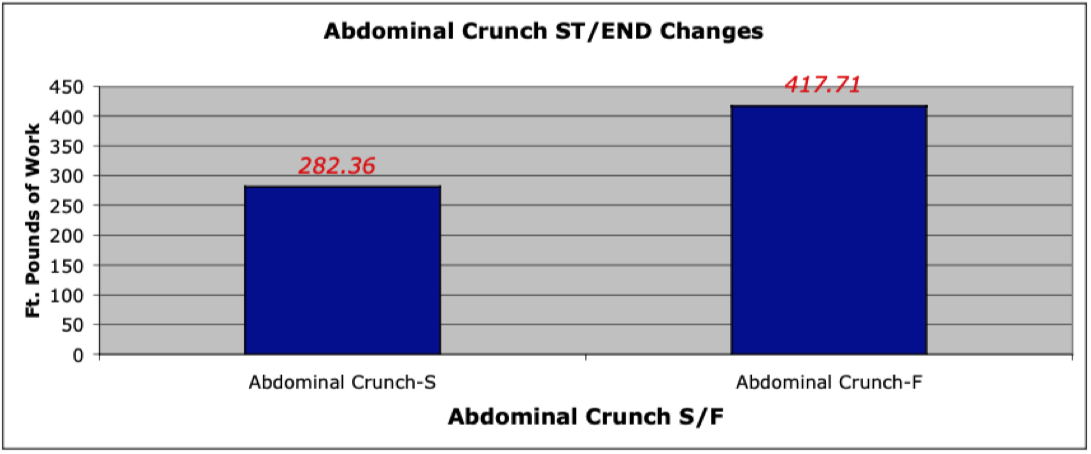

The fitness effects of a combined Pilates program and Pilates-cardio program on fitness variables. Neil Wolkodoff, et. al. The purpose of the study was to measure the effects of a combined Pilates and aerobic program, using a reformer equipped with a trampoline “rebounder” on various fitness variables. 14 subjects, (2 male, 12 female), underwent physiological testing for VO2 peak, body composition, balance, isokinetic strength, flexibility, and posture. A control group of 6 subjects (1 male, 5 female) underwent testing without any exercise intervention. After the 8-week program, parametric and independent samples t tests revealed statistically significant (p<.05), gains and improvements in VO2 (17%), Anaerobic Threshold (21%), body composition improvement/decrease (11%), gain in lean mass (5%), decrease in fat weight (15%), overall stress decrease (58%), low-back/hamstring flexibility (177%), combined hip flexion (9%), and combined torso rotation (18%). Overall strength/endurance improved (28%), as well as row (21%), knee extension (14%), knee flexion (11%), shoulder press (32%), lat pull down (28%), abdominal crunch (33%), back extension (62%) and overall strength/endurance to body weight ratio (24%). In conclusion, as measured in this study, Pilates, and specifically a combined cardio and Pilates program, provides a number of positive fitness benefits besides increased core strength and flexibility.

Introduction

As the amount of exercise required to maintain and improve health is not utilized by a majority of the population, there is a need to find exercise modalities which provide a blend of aerobic, strength and to make a physiological difference while providing a mode of exercise that appears easy to perform by the general public (64). Exercise that combines multiple benefits is especially appealing to time- conscious potential exercisers (39, 85).

Pilates has become a world-wide exercise modality which enjoys wide acceptance because of a wide array of ascribed benefits including improved strength, mobility, endurance, flexibility, core stability, proprioception, body control and even a “mind-body” effect in different gravitational planes (9, 19, 30, 80). The two most common Pilates applications are the reformer and mat-based exercises. Pilates has had acceptance and usage in the dance community, and has been proposed as a rehabilitation and training method (23, 40, 50, 51). The reformer is a best described as a longitudinal platform that uses springs or cables to provide resistance from a number of angles with both a fixed and moving platform with attachments, while mat exercises use the same principles of core and spinal alignment, yet are traditionally performed with little or no apparatus besides body weight (46). As there are well over 500 exercises that can be performed, it is difficult from a research focus to determine which exercises to utilize, as that is based upon intended results (5).

However, very little research has directly verified the popular claims of “lean muscles,” overall strength, core strength flexibility, posture and even weight loss (5,10). To date, the sparse research has looked at metabolic expenditure, in a mat not machine program, and found that in that mode of exercise, the energy expenditure could be classified as moderate at best (57, 73). Mat Pilates was used, and energy expenditure and heart rate were below ACSM guidelines. Additionally some work on EMG data from core exercises indicates that certain core exercises attain high rates of activation for the rectus abdominus (60), with one study assessing muscle groups used in a demi-plie movement (77), and another comparing swiss ball versus chair movements (1). Limited studies have demonstrated that Pilates has produced some body composition, weight loss and strength changes (69, 75, 76, 77), but in one study these changes were with young subjects and may not have been as pronounced as other forms of training (42). In another, Pilates and resistance training had almost the same benefits (63). Flexibility has been demonstrated to improve with Pilates exercise (23, 66, 69), as well as balance (43).

Trampoline-based aerobic exercise has received very little attention in the literature as a stand-alone form of endurance training. One unpublished study found that this form of exercise with very fit and leaner than average subjects produced heart rate and energy expenditure responses within ACSM guidelines when using rate of perceived exertion to set similar exercise levels between rebounding and treadmill exercise (55). Trampoline rebounding may also produce more dynamic joint movements that treadmill exercise (11). Some Pilate’s reformers have “jump boards” at the foot end of the machine, which allow movements from simple jumps to squat-like movements on a stable surface. However, the AeroPilates Pro XP555 reformer used in this study is unique in that it offers a small trampoline option.

Much of the rationale for the use of Pilates, especially with back and core issues are inference-based from physical therapy and sports medicine (16, 18, 26, 32, 54). As Pilates involves breathing patterns as well as movement, the link between diaphragmatic breathing and movement is higher in this form of exercise than some other forms of exercise (4). Additionally, other concepts in spinal stabilization such as placing the spine in neutral, activation of the deeper core muscles such as the transverses adbominus, and the practice of “hollowing” all make Pilates potentially attractive for core strengthening (33, 37, 53, 68, 72). However, little data exists that actually quantitatively measured Pilates outcomes in these variables.

Methods

Fourteen (n=14) subjects were recruited for the study with criteria of being relatively inactive for the previous 90-120 days, as defined by only one or less formal exercise session per week. Subject age range was from 23 to 64 years of age, with twelve females (n=12), and two males (n=2). Additionally, the subjects recruited on the basis of wanting to improve body composition, gain fitness and learn Pilates. All subjects completed waivers, health history and activity questionnaires (using AHA and ACSM screening/risk factors). No potential subjects were excluded based upon risk factors.

Before starting on the Pilates exercise protocol, all subjects underwent a battery of physiological tests designed to measure the progress of the subjects relative to the exercise protocol. Height and weight were recorded; with body composition assessed by skin fold measurements using the Jackson-Pollack equations. Resting Blood Pressure was assessed using an automated, medical system (Omron, Japan). Three measures were taken, with the lowest measurement recorded.

Subjects were assessed for VO2 Peak using an Oxycon Mobile (Viasys, Yorba Linda, CA), all with cycle ergometry. Each subject performed a 4-5 minute warm up with no load, then based upon body weight, resistance was increased by 10, 20 or 30 watts per minute until volitional fatigue was present correlated with an RQ of 1.10 or greater. Each subject was cooled-down to at heart rate of 110 of less before allowing them to get off the ergometer.

Balance was assessed using a Lafayette Instruments Stabilometer, model number 16030 (Lafayette, IN). This equipment allows balancing in the frontal plane, and records time in balance for 30 seconds using a degree sensitivity setting. In this case, the instrument was set to quit recording balance if the subject was more than five degrees out of balance on either side. Each subject was given one trial to understand how the apparatus worked and to experiment with foot and body position. From that point, each subject was given a 30 second trial with rest periods between each trial. The best score of the three trials was recorded.

Strength was assessed using a HydraFitness Omnitron (Belton, TX), which has capability to measure levels in chest press, row, lat pull-down, shoulder press, leg extension, leg curl and a modified core strength test (basic rectus abdominus and erector spinae through trunk flexion/extension). The apparatus was set at speed/resistance setting of “4” which approximates 160 degrees per second (68, 69). This setting was used for the assessment to measure strength/endurance changes in the subjects (8, 26, 27). Each subject was adjusted via seat distance and leg brace distance for his or her height. The test procedure was explained, and each subject was allowed to practice each movement until they felt they understood maximum speed against the particular lever arm at that speed setting.

After practice, the subject was allowed to set their own range of motion (chest press/row, shoulder press/lat pull-down and abdominal crunch/back extension), and then performed the 20 repetitions. The order for assessment was chest press/row, leg extension/leg curl, shoulder press/lat pull-down and abdominal crunch/back extension. The total foot pounds of force for the 20 repetitions was recorded, as well as the combined total for the eight measures, and that total was divided by body weight to give a strength to body weight ratio.

Flexibility was assessed using a goniometer for hip flexion and trunk rotation. For hip flexion, the subject was supine, and pulled the knee to the chest, without arm assistance, while keeping the back flat, then the score was recorded. Trunk rotation was measured from the mid-line facing forward, and subjects held a non-weighted bar to align their shoulders, in a seated position, and twisted each direction to a point just before their spine angle deteriorated or they attempted to move the bar with their shoulders. The best score for three trials was recorded for each measure.

Additionally, flexibility was measured using a standard sit and reach box (Accuflex 1), measuring in centimeters (7). Subjects, without shoes kept their legs flat against the floor while the feet were flat against the box, and placed one hand directly over the other. In a slow flexion movement, the subject pushed the measurement ruler as far as possible, then repeated the trial two more times. The best score of the three trials was recorded, and if the subject did not reach their toes, the score was recorded as negative, and if the subject could go past their toes, the score was recorded as positive.

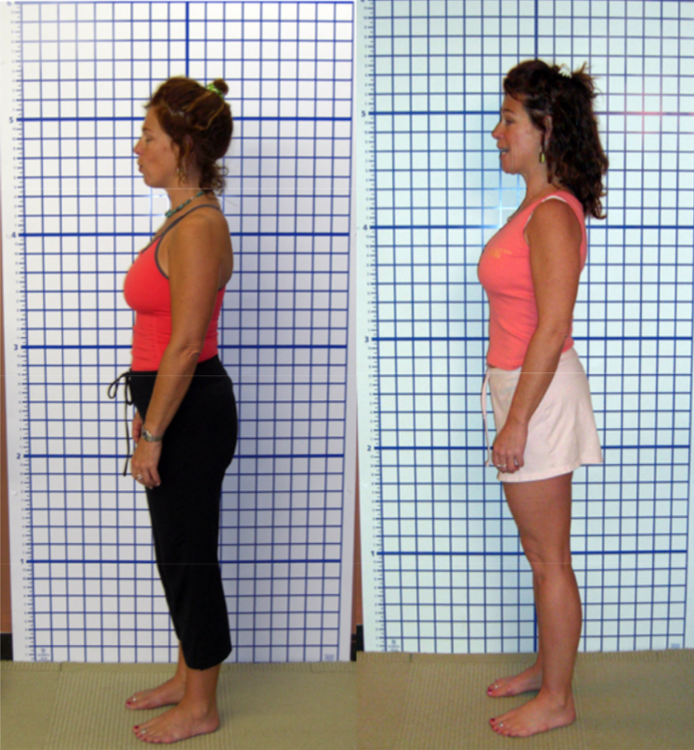

Posture was assessed visually using an Alignabod visual chart (Dallas, TX). Subjects performed this task in bare or stocking feet, and were instructed to stand in a normal posture against the posture grid. Photos were taken from front, back, and both sides before and after the exercise intervention to determine if on a visual scale the exercise regimen made a difference in overall posture.

Self-reported stress was measured using a modified professional life stress scale using 22 questions (12, 47). As the subjects recruited were all professional people, this scale uses questions about areas that relate to both work and personal life. Points are ascribed to each answer, with <15 points having low life stress, 16-30 points reflecting moderate stress, and >30 points indicating a high level of stress. Subjects were instructed to complete the questionnaire with the first responses that came to mind, then seal in envelope, and deliver at pre and post testing times. Scores were not revealed to participants.

Two sub-groups of participants also went through additional measurement to determine blood pressure response during exercise and actual energy expenditure during rebounding compared to the same relative effort on an elliptical and treadmill. Blood pressure was recorded for a five-minute segment at one-minute intervals. Energy expenditure was measured using an Oxycon Mobile measurement system. As the subjects were familiar with cardio rebounding, that was used to set a comfortable aerobic pace by level of effort and rate of perceived exertion for at least five minutes where steady state was evident. Each subject was then instructed to repeat that level of effort on a leg-only elliptical, and during treadmill walking, with measurement of energy expenditure needing to meet the five-minute minimum steady-state guideline.

Exercise Intervention

Each subject received three sessions of exercise for four weeks in a supervised environment using the AeroPilates Pro XP 555 (Stamina Fitness, Springfield, MO) After the fourth week; the individuals had one supervised exercise session, with the balance of training at home using an AeroPilates Pro XP 555. During the fourth week onward, the program for the week was introduced to the participants in a checklist form, which they returned at the beginning of the following week. Participants were instructed to perform two additional sessions on their own, and in some cases, participants performed three additional sessions. The average number of sessions for all participants for the study was 3.21 per week reflecting this fact.

As Pilates does not normally have an aerobic component, a program was devised alternating periods of five minutes of aerobic jumping with five minutes of traditional Pilate’s exercises for a total of 40 minutes of exercise. The aerobic component used various jumps starting with double leg movements, progressing to more difficult single leg movements. Initially, subjects were instructed to get comfortable with the movement, and learn how many springs or cords were required to get their effort level to a standard 6/10 on a Borg scale. During each aerobic segment, approximately five different jump patterns were alternated for the duration of this segment. After three weeks of exercise, each participant was asked to perform this portion at 40-45 jumps per minute which was chosen as an observed range for being both sustainable and below individual anaerobic threshold.

The Pilates components were divided into leg/foot work, upper body, core and flexibility components. Each exercise was repeated with the goal being 5-10 repetitions of each exercise. For the most part, widely accepted Pilates exercises were used such as hug a tree, salute, bicep curl, down circles, footwork, scooter and hamstring stretch. Participants were coached on proper form and breathing throughout each session. Modifications were made according to individual need in resistance and position as needed. More advanced exercises were added every one to two weeks for each section.

During the program, each participant was given a general set of dietary guidelines to follow for the duration of the program. However, that portion was not mandatory and there were only four individuals who tried to follow an individual dietary plan while participating in the exercise portion.

Results

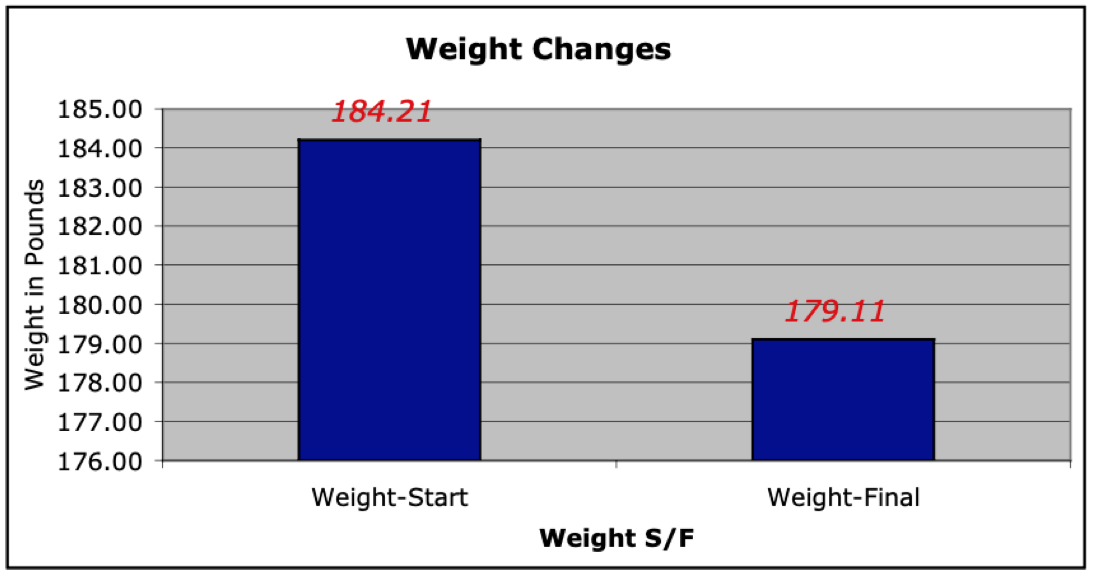

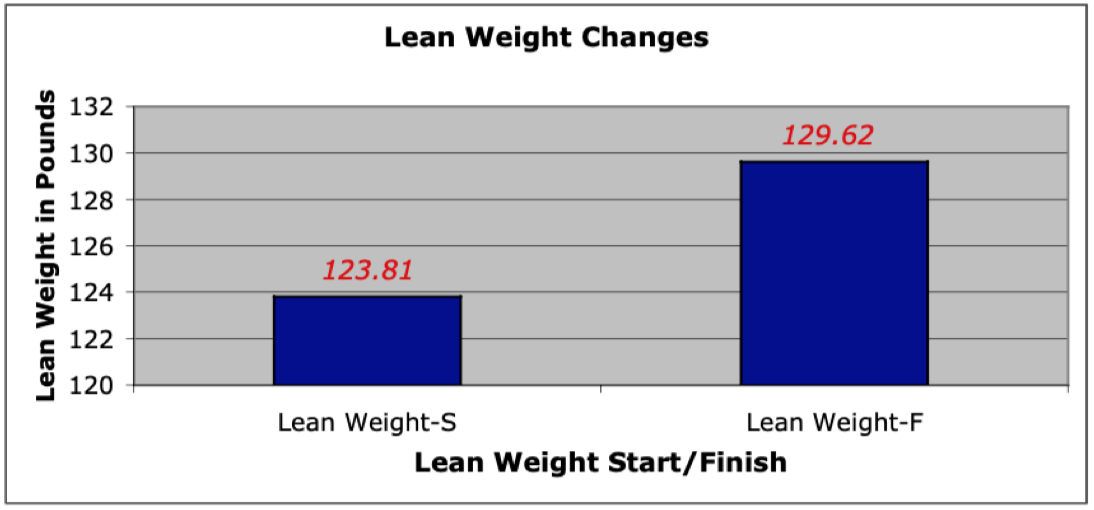

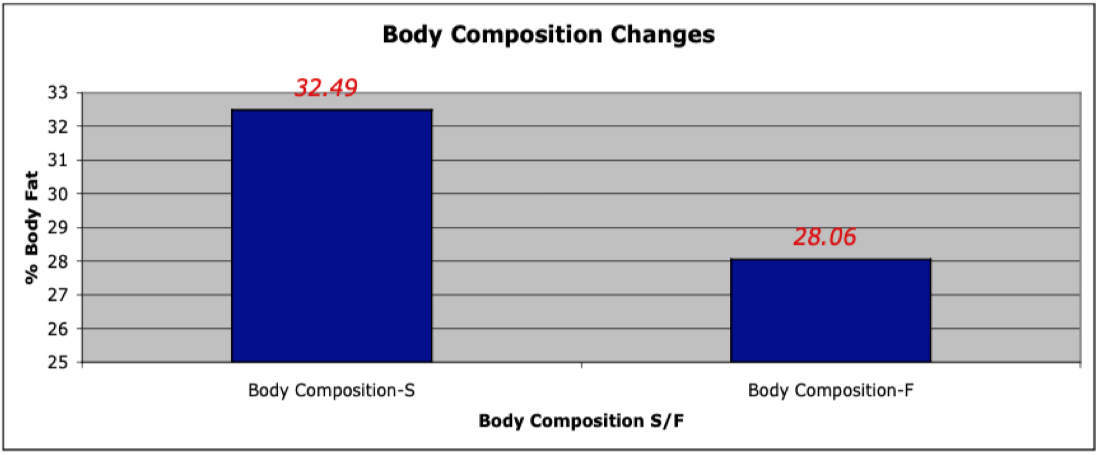

The overall results of the study are summarized in table 1. With one exception, all results were statistically significant at the .05 level. Body weight decreased for the group, and body composition improved via both a loss in fat weight and a gain in lean muscle. VO2 peak showed significant gains, with both anaerobic threshold (AT) and kcal at AT improving.

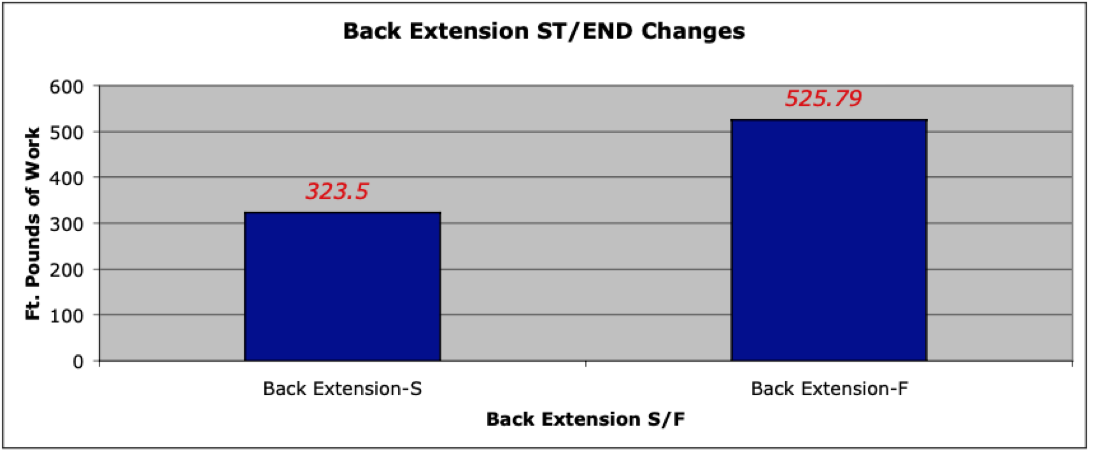

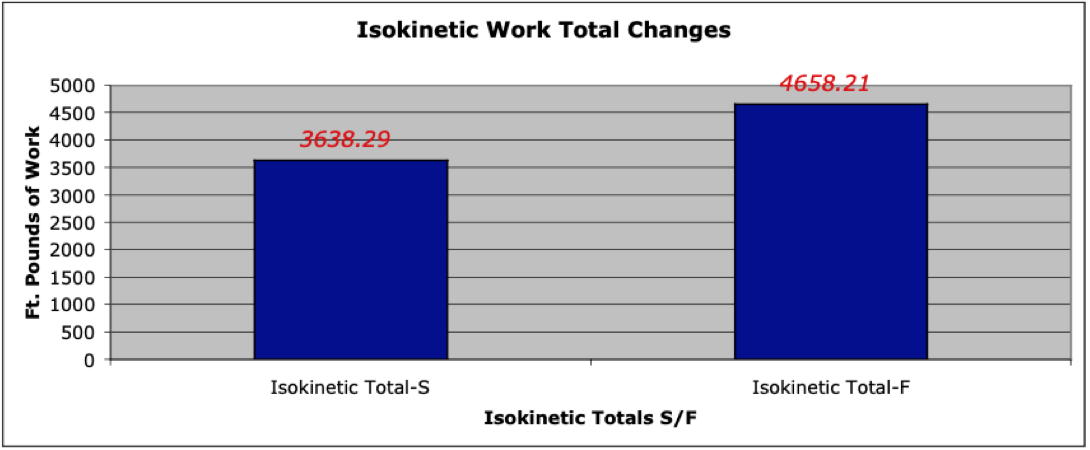

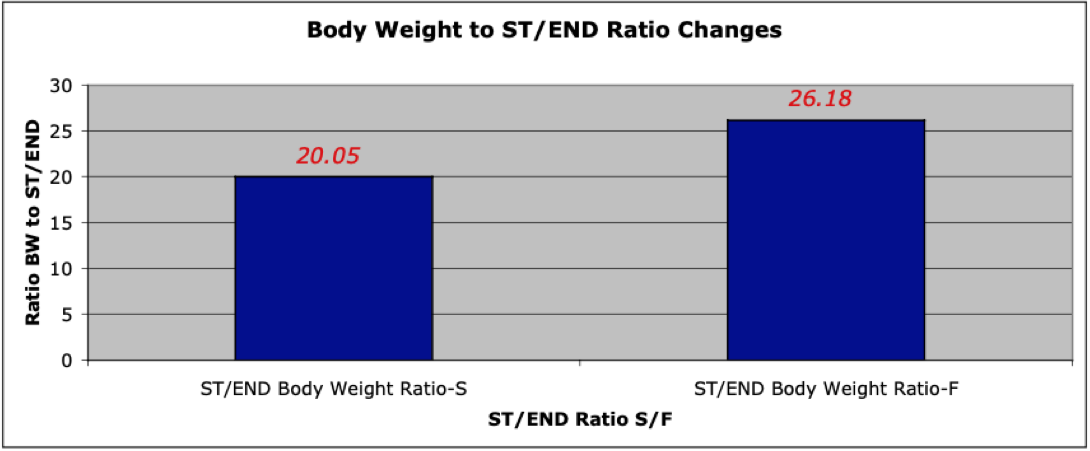

Core strength/endurance, as measured isokinetically, increased significantly, especially in back strength/endurance. Row, leg extension, leg curl, shoulder press and lat pull down measures increased significantly. Chest press measures increased yet were slightly outside the P<.05 level at .06 because of two outliers who increased their measures in slight disproportion to the group.

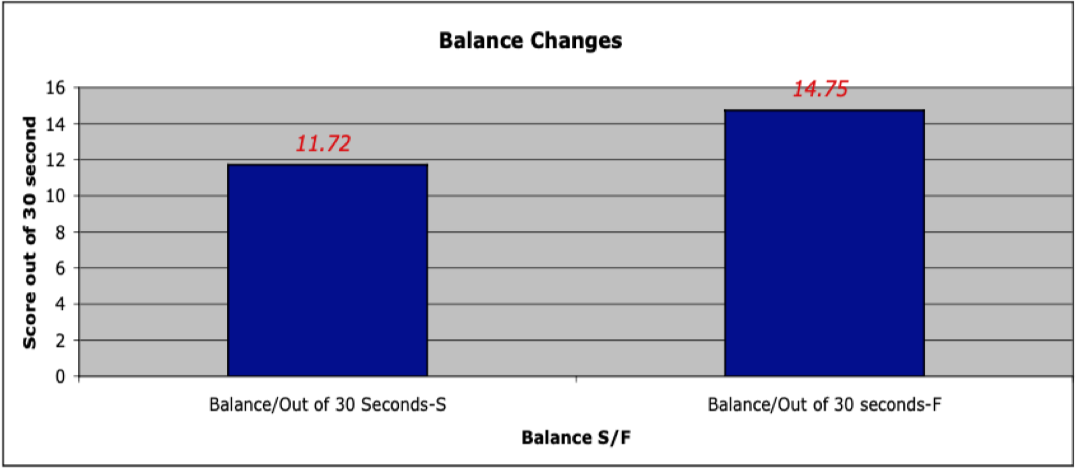

Flexibility did increase in all measures, especially notable in sit and reach measurements. One note is that on visual observation, flexibility imbalances from side to side were narrowed so at least in basic abilities, the subjects were more balanced right to left. Balance improved significantly for all subjects. Stress scales scores decreased significantly.

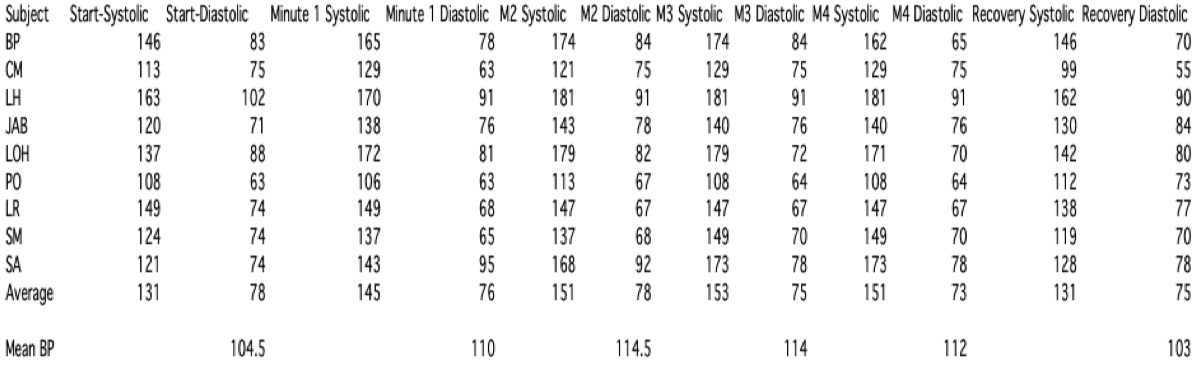

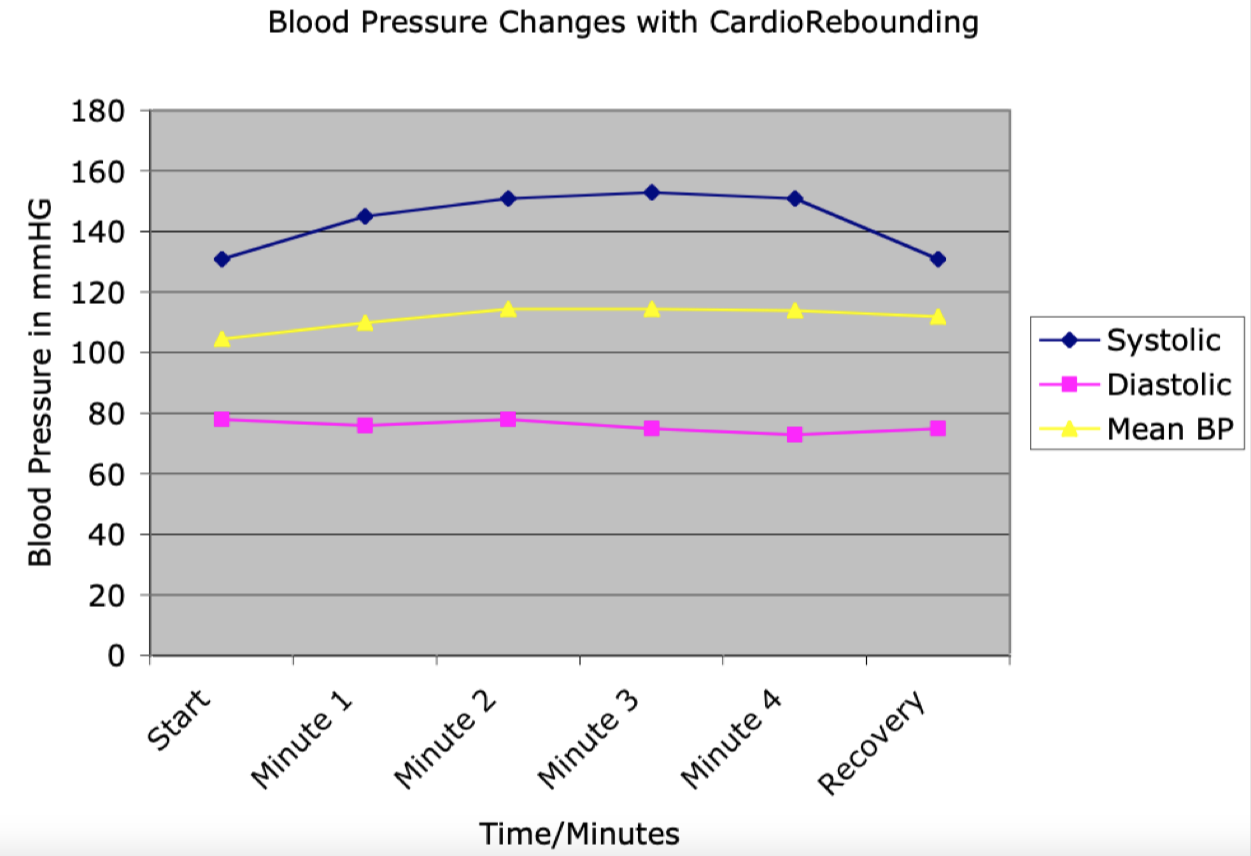

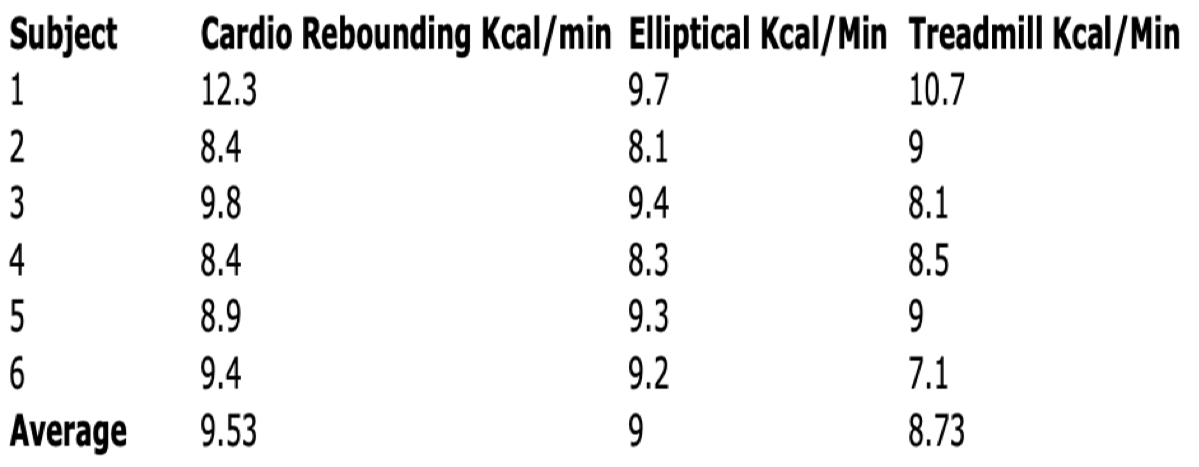

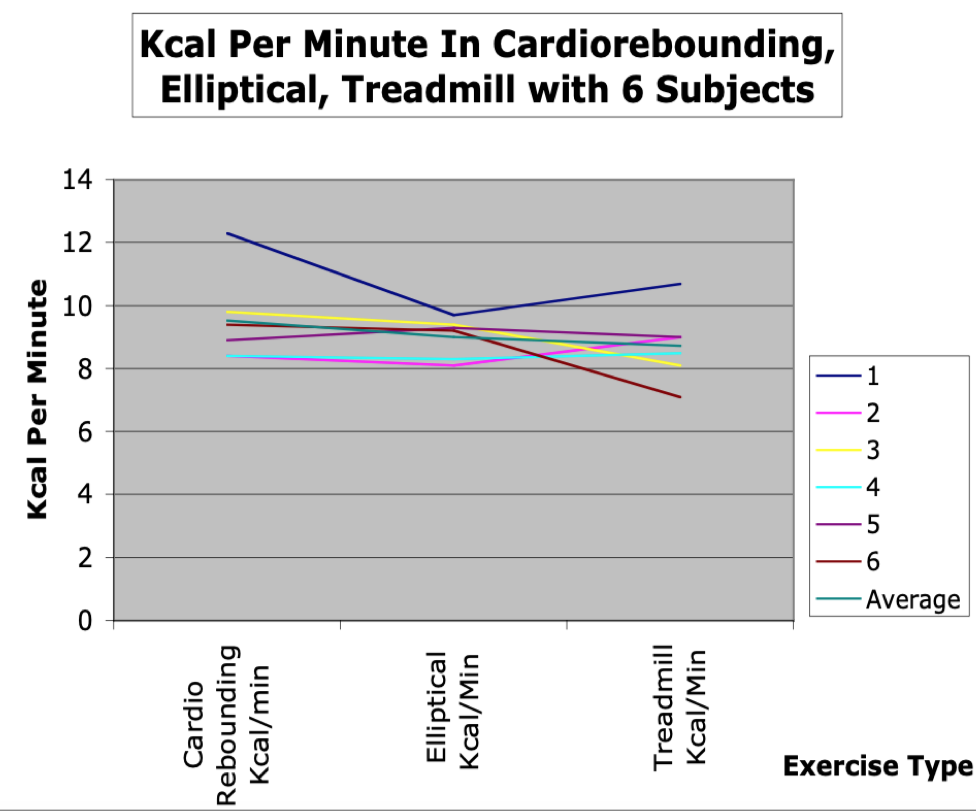

Blood pressure changes during exercise demonstrated a pattern that indicates this form of endurance exercise does not produce blood pressure responses inconsistent with other forms of endurance exercise, and therefore appear safe in terms of basic blood pressure response. Energy Expenditure during cardio rebounding compared favorably with both elliptical and treadmill exercise, and in some participants was actually higher than the elliptical or treadmill at the same rate of perceived exertion. The small sample size for these two sub-measures provides a realistic trend and estimation of results for others participating in like exercise, yet needs additional subjects to reach the same level of statistical significance found in the changes in fitness measures.

Table 1

Overall Results

Table 2

Control Group VS Exercise Intervention

Table 3

Graphic Depiction of Significant Fitness Variables

Individual Graphs for Fitness Variable Change, Start and Finish

Table 4 and 5

Blood Pressure Changes

During Cardio Rebounder

Table 6 and 7

Kcal Expenditure Cardio Rebounding, Elliptical, Treadmill

Photographic Examples

Visual Posture Assesment

Program Start

Compared to Program Finish

Discussion

The fitness improvement for the Pilates regime studied compared favorably to other forms of exercise that can be viewed as more “intense” (6, 13, 14, 15, 20, 29, 38). The exercise component performed by each subject at home had high compliance, with the subjects noting the program and progressions were easy to follow compared to previously attempted forms of exercise.

Strength/endurance increased significantly in all areas which points to the conclusion that Pilates-based exercises can contribute to activities of daily living through greater strength and endurance (62, 66). The leg extension and leg flexion scores did not increase as much as other measures. This may be due to the fact that Pilates leg movements are generally multi-joint in nature, and therefore specific quadriceps and hamstring strength gains would not be as great as muscle groups that rely on multi-joint movements, such as the row. The study also supports the notion that Pilates develops significant core strength, as demonstrated by the isokinetic results of the abdominal and back extension tests. From anecdotal reports from the subjects, core strength was needed to maintain body position during the rebounding component, so it is theorized that in part contributed to the increases of core strength/endurance as measured isokinetically.

The significant increases in VO2, or general aerobic endurance, are better when compared to other forms of moderate exercise (6, 17, 38, 59, 61). However, when compared to longer training programs, the results were comparable to programs where the length of training was significantly longer, and where training was continuous (65). This study supports the notion that for de-conditioned exercisers, cardiovascular training can occur in short, repeated bouts for almost the same benefit as continuous training. Additionally, this form of cardiovascular exercise also influenced Anaerobic Threshold and actual kcal at AT. This may be due to the fact the subjects were de-conditioned, and in some cases, they may have exceeded the recommended level of effort during this portion of their training. This has implications for weight loss programs as the higher the number of kcal which can be utilized at a relatively comfortable pace, the more kcal someone can utilize during an exercise session. As the AeroPilates XP 555 uses a trampoline instead of a “jump board,” these results are specific to the trampoline option, and may not occur with a jump board. Further study is needed to examine this relationship.

Body composition improved significantly compared to other Pilates studies, and at a level comparable to other forms of training (12, 17, 34, 42, 62, 75). It is postulated that since most of the exercises involved two or three sets combined with cardio-rebounding, this had more of an effect than if a single set of exercise was used (25, 59), both in gain of lean muscle and actual energy expenditure during the exercise session. There may have been short-term elevation of REE for a period after exercise that could be partially responsible for both weight loss and body composition improvement (14,17, 29, 59, 82, 83).

Flexibility increased, especially in low back and hip motions, all used in the training program. This was consistent with other studies where flexibility was measured (2, 66, 69, 75, 76). This needs further study, as it would appear the amount of flexibility improvement would be directly tied to the exercises used and their emphasis on increasing range of motion.

Balance improved without performing formal balance training, demonstrating the program may have a role in fall prevention and overall function by more efficient postural control (3). This may also be due to the footwork component, enabling the subjects to “tune in kinesthetically” while in either a stable or unstable situation. The balance gains were more significant than previously reported (31, 43).

While difficult to quantify, all participants felt their posture was improved. Cursory visual analysis demonstrated apparent improvements in posture even though some studies have demonstrated that not all testers will grade or analyze a subject the same way (22, 23, 35).

As Pilates is touted as a “mindful” exercise, where engagement of cognitive functions has benefits, it was not surprising that stress scores were reduced from participation in the program. The particular self-reported scale used in the study focused on a combination of work and home stresses, and as no subjects changed life situations during the study, the results were significant and indicate there may be a mind-body connection with this form of exercise reduces perceived stress (10, 30, 67).

In conclusion, the Pilates program used in this study combined with a trampoline- based aerobic program provided a sufficient training stimulus for individuals to make significant gains in VO2 Peak and associated measurements, strength/endurance, core and back strength, body composition, flexibility, and dynamic balance and appears to reduce stress via mental engagement with the exercise.

References

1. Almquist, K. L., Bopp, E.M., Yoder, C.R. (2003). EMG and motion analysis of swiss ball abdominal exercises and pilates multi-chair exercises. Thesis (M.P.T.)--University of North Dakota.

2.Aguilar, L. (1998). The effects of pilates-based training and moderate resistance plus flexibility training on muscular strength and flexibility in the elderly. Thesis (M.A.)--San Diego State University, 1998.

3.Alexander, N.B. (1994). Postural control in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jan;42(1):93-108.

4.Allison, G.T. (1998) The role of the diaphragm during abdominal hollowing exercises. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 44: 95-102.

5.Anderson, B.D. (2001). Pushing for pilates: lack of scientific research holds the movement system back, but interest in its use remains high. Rehab Management: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Rehabilitation 14 (5), 34-6.

6.Andersen RE, Franckowiak, SC, Bartlett SJ, Fontaine, KR. (2002). Physiologic changes after diet combined with structured aerobic exercise or lifestyle activity. Metabolism. Dec; 51(12): 1528-33.

7.Baltaci, G., Un, N., Tunay, V., Besler, A., and Gerçeker, A. (2003) S. Comparison of three different sit and reach tests for measurement of hamstring flexibility in female university students. Br J Sports Med 37:59-61.

8.Baltzopoulos, V., and Brodie, D.A. (1989). Isokinetic dynamometry: Applications and limitations. Sports Medicine, 8, 101-116.

9.Berardi, G. (2000). Conditioning offers ballet students ounce of prevention. Dance Magazine, 74 (11), 73.

10.Bernardo, L.M. (2007). The effectiveness of Pilates training in healthy adults: An appraisal of the research literature. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. Volume 11, Issue 2, 106-110.

11.Bhattacharya A, McCutcheon EP, Shvartz E, Greenleaf JE. (1980). Body acceleration distribution and O2 uptake in humans during running and jumping. J Appl Physiol. 49(5):881-7.

12.The British Psychological Society and Routledge Ltd., 1989. Managing Stress

13.Butts, N., & Price, S. (1994). Effects of a 12-week weight-training program on the body composition of women over 30 years of age. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 8(4), 265-269.

14.Campbell, W., Crim, M., Young, V., & Evans, W. (1994). Increased energy requirements and changes in body composition with resistance training in older adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 60, 167-175.

15.Cancela Carral JM, Ayán Pérez C. (2007). Effects of High-Intensity Combined Training on Women over 65. Gerontology. Jun 15; 53(6): 102-108.

16.Cosio-Lima, L., Reynolds, K., Winter, C., Paolone, V., and Jones, M.T. (2003) Effects of physioball and conventional floor exercises on early phase adaptations in back and abdominal core stability and balance in women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 17, 721-725.

17.Després JP, et al. (1991) Loss of abdominal fat and metabolic response to exercise training in obese women. Am JPhysiol, 261: E159- E167.

18.Donzelli S, Di Domenica E, Cova AM, Galletti R, Giunta N. (2006) Two different techniques in the rehabilitation treatment of low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eura Medicophys. 42(3):205-10.

19.Dreas, R. (2002). Ultimate pilates : achieve the perfect body shape. Carlsbad, Calif.: Hay House, Inc.

20.Fiatarone, M., Marks, E., Ryan, N., Meredith, C., Lipsitz, L., & Evans, W. (1990). High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263(22), 3029-3034.

21.Fiatarone, M., O'Neill, E., Ryan, N., Clements, K., Solares, G., Nelson, M., Roberts, S., Kehayias, J., Lipsitz, L., & Evans, W. (1994). Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. The New England Journal of Medicine, 330(25), 1769-1775.

22.Fedorak, C., Ashworth, N., Marshall, J., Paull, H. (2005). Reliability of the Visual Assessment of Cervical and Lumbar Lordosis: How Good Are We? Spine, 28(16):1857-8559.

23.Fitt, S., Sturman, J., McClain-Smith,S. (1993/94). Effects of pilates- based conditioning on strength, alignment, and range of motion in university ballet and modern dance majors. Kinesiology and Medicine for Dance, 16 (1), 36-51.

24.Frontera, W., Meredith, C., O'Reilly, K., Knuttgen, H., & Evans, W. (1988). Strength conditioning in older men: Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and improved function. Journal of Applied Physiology, 64(3), 1038-1044.

25.Galvão DA, Taaffe DR. (2005). Resistance exercise dosage in older adults: single- versus multi-set effects on physical performance and body composition. Am Geriatr Soc. Dec;53(12):2090-7.

26.Gardner-Morse, M.G., and I.A. Stokes. (1998). The effects of abdominal muscle coactivation on lumbar spine stability. Spine 23(1):86-91.

27.Grabiner, M.D., and Jeriorowski, J.J. (1991). Isokinetic trunk extension and flexion strength-endurance relationships. Clinical Biomechanics, 6, 118-122.

28.Hall, G.L., Hetzler, R.K., Perrin D., Weltman A. (1992). Relationship of timed sit-up tests to isokinetic abdominal strength. Research Quarterly Exercise Sport. 1992 Mar; 63(1):80-4.

29.Harris, K., & Holy, R. (1987). Physiological response to circuit weight training in borderline hypertensive subjects. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 10, 246-252.

30.Harvard Womens Health Watch. (2000) Exercise. Pilates incorporates mind and body. [No authors listed] Feb;7(6):6.

31.Heitkamp, HC., Horstmann, T., Mayer, F., Weller, J., and Dickhuth, H. (2001). Gain in Strength and Muscular Balance After Balance Training. Int Journal Sports Med, 22: 285-290.

32.Herrington L, Davies R. (2005) The Influence of Pilates Training on the Ability to Contract the Transversus Abdominis Muscle in Asymptomatic Individuals. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies,. Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2005, Pages 52-57.

33.Hides, J.A. et al. (2001) Long term effects of specific stabilising exercises for first episode low back pain. Spine, Vol 26: 243-248.

34.Hill, JO., Sparling, PB., Shields, TW., and Heller, PA. (1987). Effects of exercise and food restriction on body composition and metabolic rate in obese women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol 46: 622-630.

35.Hobden, J. (2000). Pilates power provides postural rehabilitation. Physiotherapy Frontline, 6 (8), 12-13.

36.Hodges, P., C. Richardson, and G. Jull. (1996) Evaluation of the relationship between laboratory and clinical tests of transverse abdominis function. Physiotherapy Research International 1(4):269.

37.Hodges P.W., Richardson, C.A. (1996) Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine, Vol 21: 2640- 2650.

38.Hunter, G., Byrne, N., Gower, B., Sirikul, B. and Hills, A. (2006). Increased Resting Energy Expenditure after 40 Minutes of Aerobic But Not Resistance Exercise. Obesity 14: 2018-2025.

39.Hurley, B. (1994). Does strength training improve health status? Strength and Conditioning Journal, 16, 7-13.

40.Hutchinson, M.R., Tremain, L., Christiansen, J., Beitzel, J. (1998). Improving leaping ability in elite rhythmic gymnasts. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 10, 1543-7.

41.Jackson, A.W., and Dishman, R.K,. (2000). Perceived submaximal force production in young adult males and females. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 448-451.

42.Jago R., Jonker M.L., Missaghian, M., Baranowski, T. 2006. Effect of 4 weeks of Pilates on the body composition of young girls. Prev Med. Mar;42(3):177-80.

43.Johnson, E.G., Larsen, A., Ozawa, H., Christine A. Wilson, C.A., Kennedy, K.L. (2007). The effects of Pilates-based exercise on dynamic balance in healthy adults. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. Volume 11, Issue 3, Pages 238-242.

44.Judge, J.O., Lindsey, C., Underwood, M., and Winsemius D. (1993). Balance improvements in older women: effects of exercise training. Phys Ther. Apr;73(4):254-62; discussion 263-5.

45.Lange C, et al. (2000). Maximizing the benefits of Pilates-inspired exercise for learning functional motor skills. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 4(2), 99-108.

46.Latey, P. (2001). The pilates method: history and philosophy. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 5 (4), 275-282.

47.Lefcourt, H.M. (1982) Locus of control: Current trends in theory and research. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

48.Liebenson, C. (1997). Spinal stabilization Training: The therapeutic alternative to weight training. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. Volume 1, Issue 2, January: 87-90.

49.Kiley, G. (1999). Pilates and sports performance. Sports Coach, 22 (1) 36.

50.Levine B, Kaplanek B, Scafura D, Jaffe WL. (2007). Rehabilitation after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a new regimen using Pilates training. NYU Hosp Jt Dis;65(2):120-5.

51.Loosli, A.R., & Herold, D. (1992). Knee rehabilitation for dancers using a pilates-based technique. Kinesiology and Medicine for Dance, 14 (2), 1-12.

52.Lugo-Larcheveque N, Pescatello L.S., Dugdale T.W., Veltri, D.M., Roberts W.O. (2006). Management of lower extremity malalignment during running with neuromuscular retraining of the proximal stabilizers. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2006 May;5(3):137-40.L

53.Maher C.G., (2004). Effective physical treatment for chronic low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. Jan;35(1):57-64.

54. McGill, S. (2003). Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2003.

55.McGlone, C., Kravitz, L., Janot, J.M. A Low Impact Alternative. Freedom Spring System, No Publication Date.

56.McLain S, Carter CL, Abel J. (1997).The effect of a conditioning and alignment program on measurement of supine jump height and pelvic alignment when using the Current Concepts reformer. J Dance Med. 1(4):149-154.

57.McMillan, A., Proteau, L., & Lebe, R. (1998). The effect of pilates- based training on dancers' dynamic posture. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 2 (3), 101-107.

58.Meeus, C. and Searle, S. (2001). Secrets of pilates. London: DK Publishing.

59.Melby, C., Scholl, C., Edwards, G. and Bullough, R. (1993). Effect of acute resistance exercise on post-exercise energy expenditure and resting metabolic rate. Journal of Applied Physiology, Vol 75, Issue 4 1847-1853.

60.Olson, M., and Smith, C.M. 2005. Pilates exercise: lessons from the lab: a new research study examines the effectiveness and safety of selected pilates mat exercises. IDEA Fitness Journal.

61.Olson, M.S., H.N. Williford, H.N., R. Martin, R. (2004) The energy cost of a basic, intermediate, and advanced Pilates’ mat workout. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 36(5)(Suppl.):S357.

62.Otto, R., Yoke, M. McLaughlin, K., Morrill, J., Viola, A., Lail, A., Lagomarsine, M., Wygand, J. (2004). The Effect of Twelve Weeks of Pilates vs Resistance Training on Trained Females. [Annual Meeting Abstracts: H-25 - Free Communication/Poster: Stretching]. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: Volume 36(5) Supplement: S356- S357.

63.Parrott, A.A. (1993). The effects of pilates technique and aerobic conditioning on dancers' technique and aesthetic. Kinesiology and Medicine for Dance, 15 (2), 45-64.

64.Perri, M.G., Anton, S.D., Durning, P.E., Ketterson, T.U., Sydeman, S.J., Berlant, N.E., Kanasky, W.F., Newton R.L., Limacherm M.C., Martin, A.D. (2002). Adherence to exercise prescriptions: effects of prescribing moderate versus higher levels of intensity and frequency. Health Psychololgy. Sep;21(5):452-8.

65.Pollock, M.L. (1973). Quantification of endurance training programs. Exercise and Sport Science Reviews, 1, 155-188.

66.Porcari, J.P. and Spilde, S. (2005). ACE-sponsored study: Can Pilates Do It All? ACE Fitness Matters, November/December: 10-11.

67.Pratley, R., Nicklas, B., Rubin, M., Miller, J., Smith, A., Smith, M., Hurley, B., & Goldberg, A. (1994). Strength training increases resting metabolic rate and norepinephrine levels in healthy 50 to 65 year-old men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 767, 133-137.

68.Risch, S., Nowell, N., Pollock, M., Risch, E., Langer, H., Fulton, M., Graves, J., & Leggett, S. (1993). Lumber strengthening in chronic low back pain patients. Spine, 18, 232-238.

69.Rogers, K., and A.L. Gibson. (2006) Effects of an 8-week mat Pilates training program on body composition, flexibility, and muscular endurance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 38(5):S279- S280.

70.Russell, J. R., Strong, L. R., Meins, J. D. (1992). Developing a reliable testing protocol for the Hydra Fitness Upper Body OmniTron. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 16(2), 87-91.

71.Russell, J. R., Little (Strong), L. R., and Meins, J. D. (1991). Reliability and testing protocol development for a hydraulic strength device.[Abstract]. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 23(4), S95.

72.Rydeard, R., A. Legar, and D. Smith.(2006) Pilates-based therapeutic exercise: effect on subjects with nonspecific chronic low back pain and functional disability: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 36(7):472-484.

73.Sapsford, R.R., and P.W. Hodges.(2001) Contraction during abdominal maneuvers. Archives Rehabilitation 82:1081-1088.

74.Schroeder J.M., et al. (2002) Flexibility and Heart Rate Response to an Acute Pilates Reformer Session. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34:5.

75.Segal NA, Hein J, Basford JR. (2004). The effects of Pilates training on flexibility and body composition: an observational study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Dec;85(12):1977-81.

76.Sekendiza, B., Altuna, O., Korkusuza, F., Akın, S. (2007). Effects of Pilates exercise on trunk strength, endurance and flexibility in sedentary adult females. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. Volume 11, Issue 4, October, Pages 318-326.

77.Self, B.P., Bagley, A., and Paulos, L. (1996). Functional biomechanical analysis of the pilates-based reformer during demi-plie movements. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 12 (3), 326-337.

78.Sewright, K., Martens, D.W., R.S. Axtell, R.S. (2004) Effects of six weeks of pilates mat training on tennis serve velocity, muscular endurance, and their relationship in collegiate tennis players. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 36(5)(Suppl.):167.

79.Singh, N., Clements, K., & Fiatarone, M. (1997). A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. Journal of Gerontology, 52A(1), M27-M35.

80.de Souza, M.S., Vieira, C.B. (2006). Who are the people looking for the Pilates method? Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 10: 4: 328-334.

81.Stewart, K., Mason, M., & Kelemen, M. (1998). Three-year participation in circuit weight training improves muscular strength and self-efficacy in cardiac patients. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation, 8, 292-296.

82.Stone, M., Blessing, D., Byrd, R., Tew, J., & Boatwright, D. (1982). Physiological effects of a short-term resistive training program on middle-aged untrained men. National Strength and Conditioning Association Journal, 4, 16-20.

83.Takeshima N., Rogers, M.E., Islam, M.M., Yamauchi, T., Watanabe, E., and Okada, A. (2004). Effect of concurrent aerobic and resistance circuit exercise training on fitness in older adults. Eur J Appl Physiol. Oct;93(1-2):173-82.

84.Tremblay A., Fontaine E, Poehlman ET., Mitchell D., Perron, L., and Bouchard, C. (1986). The effect of exercise training on resting metabolic rate in lean and moderately obese individuals. International Journal of Obesity. 10(6):511-7.

85.Westcott, W., & Guy, J. (1996). A physical evolution: Sedentary adults see marked improvements in as little as two days a week. IDEA Today, 14(9), 58-65.

written by Marjolein Brugman

written by Marjolein Brugman

Marjolein Brugman is the founder of lighterliving and Aeropilates. “lighterliving is a movement and lifestyle choice we can all make. Let’s make it simple – make one decision a day to be better and watch the small steps lead to big changes. Eat smart, stay active, and you’ll live to feel a lighter life."